Drilling Company Hasn’t Released Chemical List More Than A Month After Drinking Water Contamination

More than a month after unapproved chemicals were illegally dispersed into drinking water aquifers, 85 – 90% of the chemical mixture is still unknown. The chemicals were part of a “surfactant solution” used for a drilling operation by JKLM Energy, LLC at its Reese Hollow 118 well pad in Potter County, Pennsylvania.

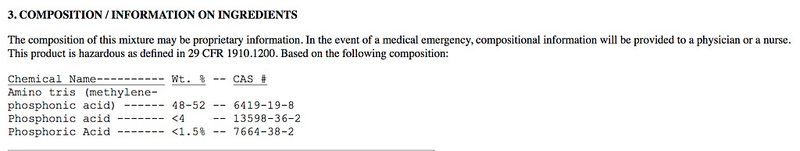

Potter County resident Les Rolfe takes notes about his drinking water complaint investigation during a phone call with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) following the JKLM Energy, LLC Reese Hollow chemical spill. For more on this story read Part 4 of Public Herald’s INVISIBLE HAND series. © Joshua B. Pribanic

Public Herald recently learned that some area residents living inside the potential ‘zone of contamination’ still have not been notified of the polluted groundwater by authorities who’ve responded to the incident, which included local Emergency Services, JKLM Energy, and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

No Notification, No Testing for Neighbor

Harry Sickler lives on Morley Drive near JKLM’s Reese Hollow 118 well pad in Sweden Township where chemicals first entered the groundwater aquifer. According to him and a neighbor, another home across the road from their small development was confirmed for contaminated drinking water.

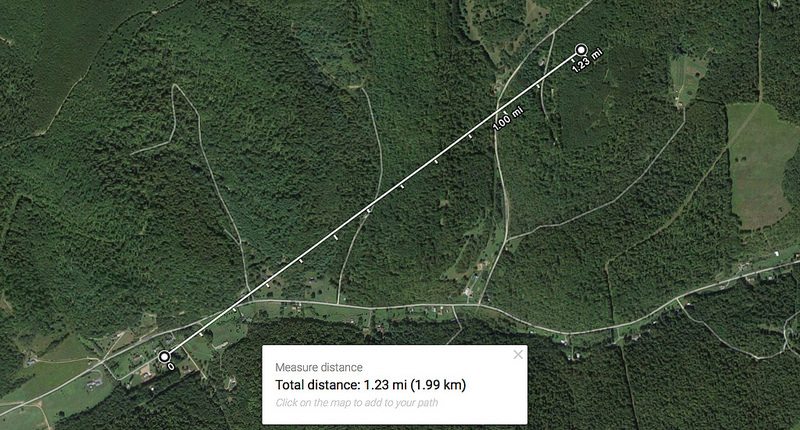

“I can see the house from my property,” Sickler told Public Herald, though he doesn’t know exactly how far from his affected neighbor he is. “I’m closer to the well pad than the house that had bad water. I thought they’d come to test the water, but I haven’t been contacted by JKLM or DEP.”

The approximate distance of Harry Sickler’s home to the Reese Hollow well pad is 1.23 miles, while the plume of contamination has been recorded as far as 2.8 miles. © Public Herald

Another one of Sickler’s neighbors, who wished to remain off the record, said that the company tested their water soon after problems started. The test didn’t reveal contaminants of concern, and the homeowner hasn’t heard anything else about testing. It’s unclear why Sickler’s neighbors were notified and had water tested, but his family wasn’t, even though they live in the same neighborhood.

“I work at night, so I’m home every day. Nobody came, no one left a note or anything,” said Sickler.

Sickler found out about the groundwater contamination through word-of-mouth, updates on a local blog called Solomon’s Words For The Wise, and from a breaking report by Public Herald.

Retired veterinarian Dr. Ronnie Schenkein heard about the contamination the same way as Sickler – neither received any official public notification to residents in the area.

Schenkein lives about two miles from JKLM’s operation and became concerned after chemicals were detected in water 9,000 and 14,000 feet from the gas well. About a month after groundwater contamination occurred, Schenkein told Public Herald that her neighbor still hadn’t known there was a problem with water in the area.

“It’d be great if county officials had a system of rapid notification for people in the vicinity of any potential spills,” Schenkein told Public Herald. “We do not know at what rate or how far contaminants will spread or how much they’ll be diluted, wherever they go. People who’ve worked hard all their lives are worried about losing their property value. Our livelihoods are in their hands.”

No News = Good News?

Keeping the public in the dark isn’t new, especially for the industry and DEP. The oil and gas industry has long enjoyed special exemptions from federal and state law that allow them to keep the chemical mixtures they use for hydraulic fracturing a secret. And according to Public Herald’s recent 30-month complaint report, DEP has a proven history of keeping polluted drinking water “off the books.”

Sickler happens to also work at Charles Cole Memorial Hospital, which manages its own public water supply, which had to be taken offline after JKLM reported the Reese Hollow incident. “No one notified us about the hospital’s water either,” Sickler said. “Same thing, I heard it from word-of-mouth. Otherwise I had no idea anything happened.”

Cole Memorial’s water supply was taken offline as a “precaution” during the week after chemicals were discovered in groundwater that serves as a source for the hospital’s supply. Luckily for the hospital, another public water source nearby, managed by Coudersport Borough Water Authority, was able to serve as a backup.

Unfortunately, Coudersport Borough also had to shut down one of its water supplies across the street from the hospital and switch to one now being used by both the borough and hospital. According to DEP, both public water supplies are still offline and being tested.

Potter County Department of Emergency Services was notified of the incident and responded as well. Fire Chief Bryan Phelps stated at an October 5th Sweden Township Meeting that local officials responded thoroughly, did everything they “were supposed to do,” and that the law does not require public notification in the event of drinking water contamination.

“Sometimes you start talking about things and that’s how rumors get started. You don’t want to cause alarm,” stated Sweden Township Supervisor Jonathan Blass when asked if officials planned to notify the public via U.S. Mail or another method, even though they weren’t required to by law.

But what causes more alarm – knowing more or knowing less? How should people be notified?

Potter County Department of Emergency Services has a Facebook page it regularly updates, but since contamination began on September 18th, there hasn’t been a single mention of the water pollution of aquifers found in its feed.

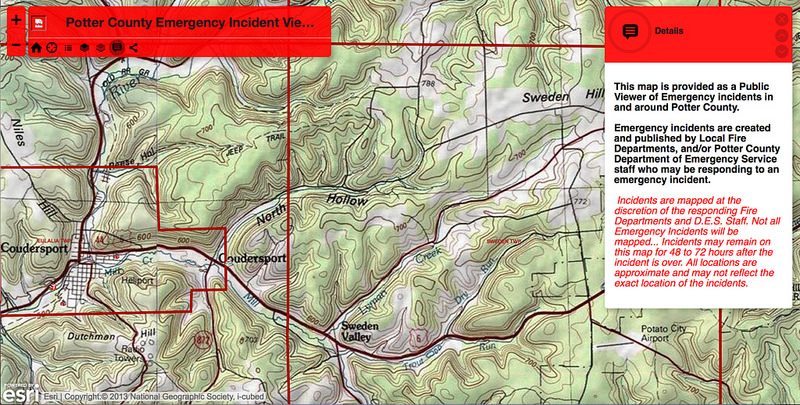

Potter County Emergency Service’s website also links to an “Emergency Incident Viewer” which also has no record of the water contamination but does have a disclaimer: “Incidents are mapped at the discretion of the responding Fire Departments and D.E.S. [Dept. of Emergency Services] Staff. Not all Emergency Incidents will be mapped…”

A screenshot of Potter County Emergency Viewer gives no indication that groundwater used for public and private water supplies has been polluted by chemicals during JKLM Energy drilling operations.

JKLM’s “Trade Secrets”

JKLM has identified three substances used during operations that are known to have contaminated groundwater – isopropanol, methyl blue active substance (MBAS) and “Rock Oil” – as well as acetone, a byproduct created by the breakdown of isopropanol in the environment.

However, JKLM Energy declined to provide the full list of chemicals used during their operation to Public Herald, Potter Leader Enterprise, public officials and residents. The company offered no explanation for not disclosing their full list of chemicals.

Under a 2005 federal exemption to the Safe Drinking Water Act, oil and gas companies are not required to reveal the chemicals injected underground at high pressure for hydraulic fracturing – or fracking. Only diesel fuel, when injected for fracking, has to be disclosed to regulators. This exemption earned the nickname “Halliburton Loophole” because then Vice President and former Halliburton CEO Dick Cheney reportedly influenced the legislation to benefit the oil and gas industry.

But JKLM wasn’t fracking when it contaminated water in Potter County – it was drilling – so it’s unclear whether the “Halliburton Loophole” exemption even applies.

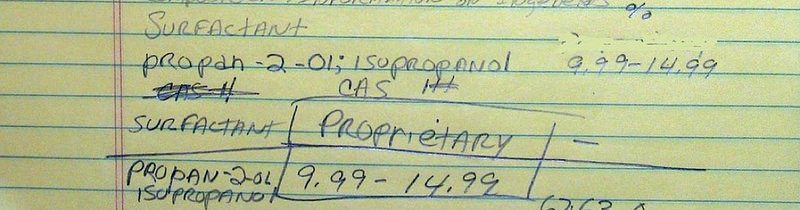

According to DEP, isopropanol made up only 10-15% of the surfactant JKLM used, identified as “F-485”. The rest of the mixture is listed as “proprietary” on Safety Data Sheets. The sheets were accessed via Right-to-Know request by Save Our Streams PA co-founder Laurie Barr to the Pennsylvania Department of Labor.

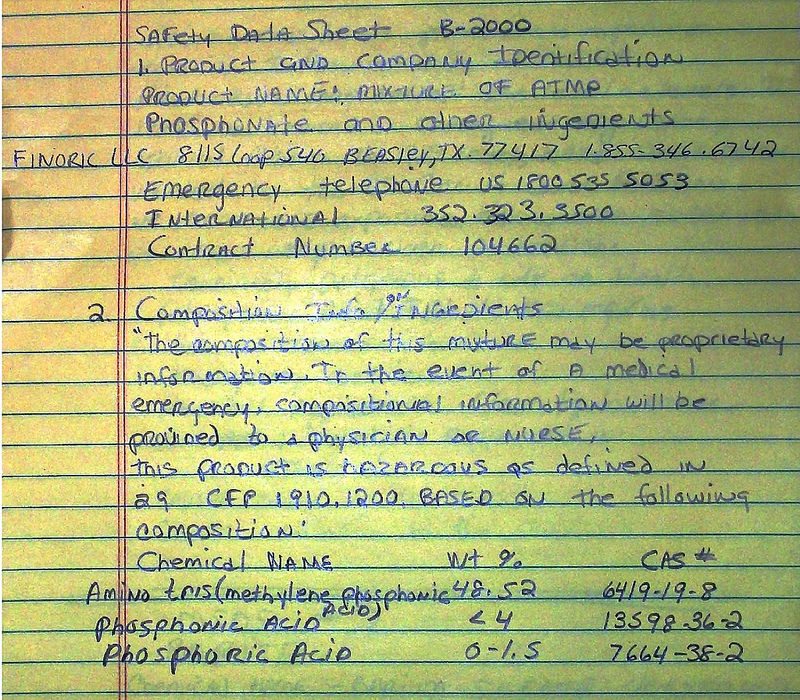

In order to obtain the list of chemicals, Barr was instructed to drive to Potter County Emergency Management Services in Coudersport and copy all information by hand. She was not permitted to photocopy, photograph or scan any of the records, which runs contrary to standard permissions granted under the Right-to-Know Law.

Notes taken by Laurie Barr during her file review. © Public Herald

Despite ‘trade secret’ obstacles, Barr managed to create a list of at least some of the chemicals JKLM had at its well site through her Right-to-Know request. Her list doesn’t reveal all chemicals, or which ones were pumped underground, but it is the most comprehensive list of chemicals used by the company compiled to date, providing more information about the full list of chemicals to the public than the Department of Environmental Protection, JKLM Energy, or either of the two public water suppliers.

“It’s important to remember that this list of chemicals only includes ones that equalled 1,000 gallons or more,” Barr told Public Herald. “Anything less than 1,000 gallons isn’t required to be reported to the Department of Labor. Isopropanol, the ‘chemical of concern,’ was only used at 98 gallons and rock oil at 35 gallons. What other chemicals were onsite under reportable amounts – we still don’t know.”

One chemical listed for JKLM’s operations is “B-2000” supplied by Finoric LLC, based in Texas. The product’s name on the SDS is “Mixture of ATMP Phosphonate and other ingredients.” Under “Ingredients” it reads: “The composition of this mixture may be proprietary information. In the event of a medical emergency, compositional information will be provided to a physician or a nurse.”

Only about 48-52% of B-2000’s composition is identified.

Screenshot of Safety Data Sheet for B-2000 from Finoric LLC, reported by JKLM Energy as a chemical on site during their operations.

JKLM’s History Of Violations

On September 22nd and September 30th, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has issued six Notices of Violation to JKLM for failing “to construct and operate a well…to ensure the integrity of the well is maintained and the health, safety, environment and property are protected” as well as “pollution of Waters of the Commonwealth.”

JKLM’s violations include failing to have an Emergency Response Plan submitted prior to operations, generating industrial waste without a Control and Disposal Plan, a reported 275 gallon spill of phosphonic acid and another estimated 63 gallon spill of calcium chloride.

After a month of investigations, the identity of JKLM personnel responsible for making the decision to pump unapproved, chemical substances down an uncased shale gas well bore is still a mystery. In an October 7th interview with Potter Leader Enterprise, JKLM’s public relations officer revealed that the company was still investigating who at the company was responsible.

In a story by the Bradford Era last week, JKLM has applied for additional drilling permits within the county amid ongoing investigations.

Water Tests vs. Chemicals Used

Private water supplies in the area have been tested by JKLM Energy and DEP’s Bureau of Oil and Gas. Public water supplies are tested by DEP’s Bureau of Safe Drinking Water.

At a local meeting of county officials regarding water quality on October 18th, director of Emergency Services and Potter County Commissioner Doug Morley reported that he was unaware of the full list of chemicals JKLM used.

As Barr told Public Herald, “I live in Coudersport and drink the water that will soon come from the impacted aquifer. I was shocked to learn that our local officials and DEP’s Bureau of Safe Drinking Water, who is testing our public water supply, are not aware of all the chemicals JKLM is using.”

Public Herald called the Bureau of Safe Drinking Water and confirmed with DEP’s John Hamilton that his bureau does not work with DEP’s Bureau of Oil & Gas, and therefore he is unaware of all the chemicals used by JKLM.

“Even if we had a full list of chemicals, it doesn’t mean we’d test for all of them,” Hamilton told Public Herald. “We’d still need to assess the potential for risk and then decide which ones we needed to test for.”

When asked where test results of the public water supply could be accessed, Hamilton said, “The general public cannot access water test results online, you’d have to do schedule a file review.”

According to Hamilton, DEP doesn’t have a policy to give test results directly to the public water authorities where they conduct testing. “Same goes for them, typically in order to get those results the public water supplier would have to do a file review,” he said.

Just because JKLM had a chemical on site doesn’t mean the company put it down ‘the hole.’ However, as long as JKLM withholds the secret recipe of the surfactant solution it introduced into aquifer, no one will know for sure.

If the chemicals that JKLM uses in the fracking of it’s wells are so safe for the environment and the public, why won’t they tell the DEP and the public? Why is JKLM hiding behind the Halliburton Loophole if these chemicals are so safe? Acts of god are not permitted with fracking, accidents will happen with the “produced water,” “well brine,” and “fracking waste.” Waste haulers are tempted to just dump it along the road, because they have so much waste to get rid of and fewer places to dump it, and the profits so much at risk, it is too easy to cut corners, to maximize profits. Murphy’s law is always at play here and Murphy was an optimist. How much profit is enough for JKLM? Why is DEP with holding information from water testing from the public? Is the DEP really doing its job or is it hampered by lack of funding, staffing, and environmental law or is it the department that you “Don’t Expect Protection” from because they have been corrupted by the industry?

Melissa, you wrote “Schenkein lives about two miles from JKLM’s operation and became concerned after chemicals were detected in water 9,000 and 14,000 feet from the gas well.” That’s almost 3 miles – a long distance. Can you say which chemicals?

Hi Paul. The chemical detected by JKLM Energy in the Hershey Pond about 14,000 feet away was MBAS. Though the company claimed it would release the remaining test results for the pond at a later date, to my knowledge, those tests have not been made public.

http://nebula.wsimg.com/9ca3a9d02b06e7a21e7ab4c85c8e6e14?AccessKeyId=42212B4F0081E5B9A0BD&disposition=0&alloworigin=1

It is indeed a long distance.

Thanks. Wow, so JKLM says “JKLM is continuing to work [to] restore the local water aquifer to pre-drilling quality.” Is that possible, once it’s contaminated?